I struck up a conversation with John when I spotted the book he was collecting from the request desk. Task for Coastal Command by Hector Bolitho is a pretty obscure tome – not the sort of book your average aviation enthusiast would seek out. As it turned out my fellow borrower was no ordinary aviation enthusiast. A flier with a long and unusual career in the Royal Navy behind him, Captain J.L.Williams, R.N. (Ret’d) flew an astonishing range of aircraft before hanging up his bone-dome in 2018. While today’s interviewee isn’t an ‘Atypical Simmer’ in the conventional sense I think what follows will interest anyone who has ever gripped a collective, thumped a round-down, ridden a thermal or reached for an ejection seat handle in Simulatia.

John grew up in a village near Wolverhampton during the thirties and early forties and remembers looking out from a back-garden Anderson shelter at a night sky illuminated by the glow from blitzed Coventry. Fascinated by aircraft from an early age, he learnt to fly courtesy of an RAF ATC flying scholarship, but ended up joining the Senior Service’s engineering branch on leaving school in 1950. Six years later, a qualified marine engineer specialising in aeronautical engineering, he commenced an RN flying career that coincided with those of shapely sea shadowers such as the Sea Hawk, Scimitar, and Buccaneer.

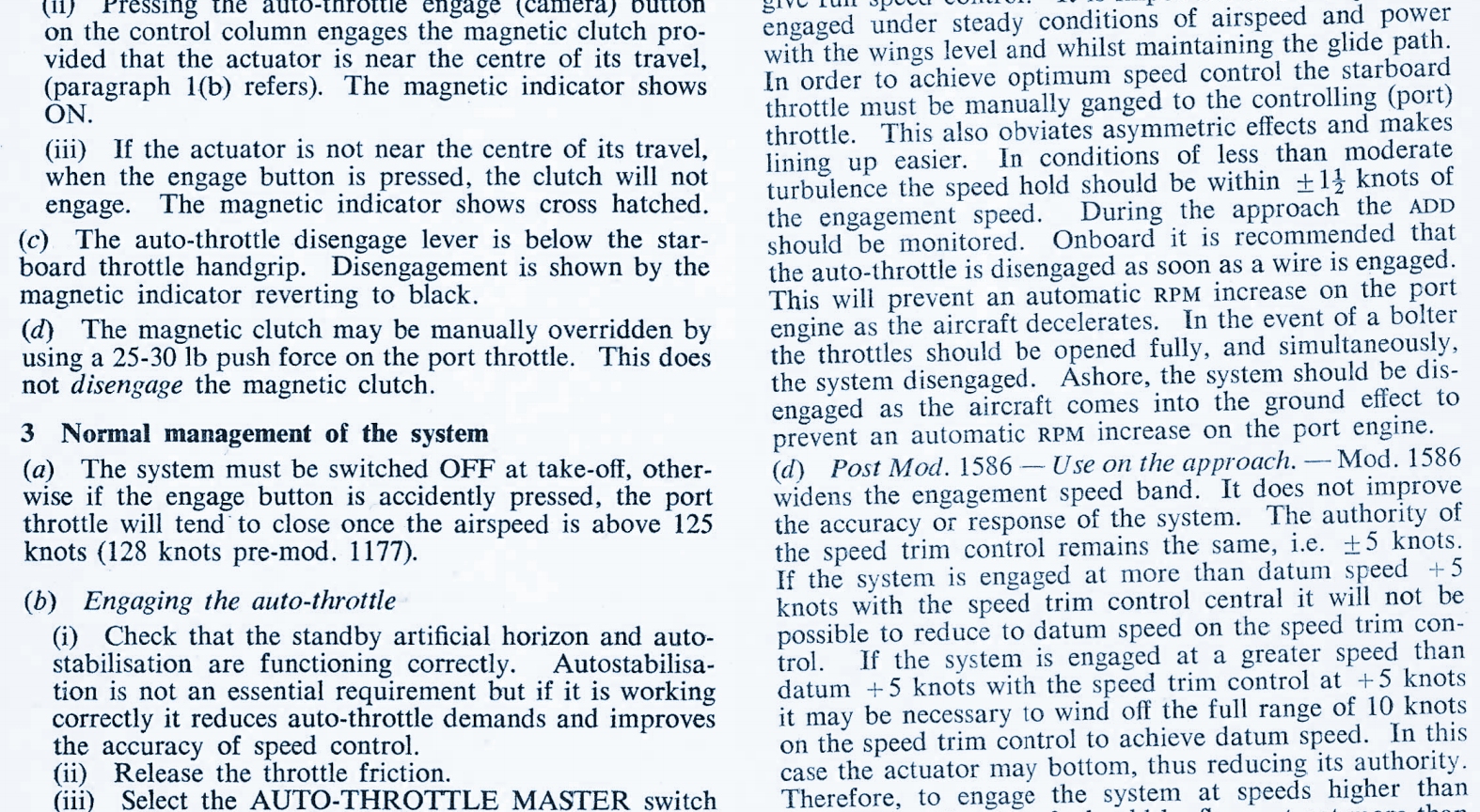

His relationship with whirlybirds began at Farnborough in 1962, as did as his move into test flying. Appointed to the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Bedford as the naval test pilot, he was involved in a series of catapult launch, arresting, autothrottle and head-up deck landing approach trials before packing his duffel bag for Singapore and a new role as a V.I.P. helicopter pilot and maintenance test pilot on fixed and rotary wing aircraft.

By the late sixties he was back in the UK flight testing naval helicopters. Following this were spells as Air Engineer Officer on carriers HMS Eagle and HMS Hermes, periods in command of both the Royal Naval Aircraft Yard at Wroughton and Fleetlands, and time at Boscombe Down as the senior helicopter test pilot. By the time of his retirement in 1987, John was in charge of all air engineering activity in the Fleet and Royal Fleet Auxiliary service.

His appetite for aviation as keen as ever, John took a post as Project Manager with Edgely, the Wiltshire company behind the distinctive Optica, after leaving the Navy. For two memorable years he was involved in customer support, and ferry and demonstration flying in the U.K., Belgium, Egypt, Jordan, Dubai and Spain. He’s currently writing his memoirs when not fielding questions put to him by curious/curious RPS columnists. RPS: How many aircraft types have you have flown in total? (A list would be lovely)

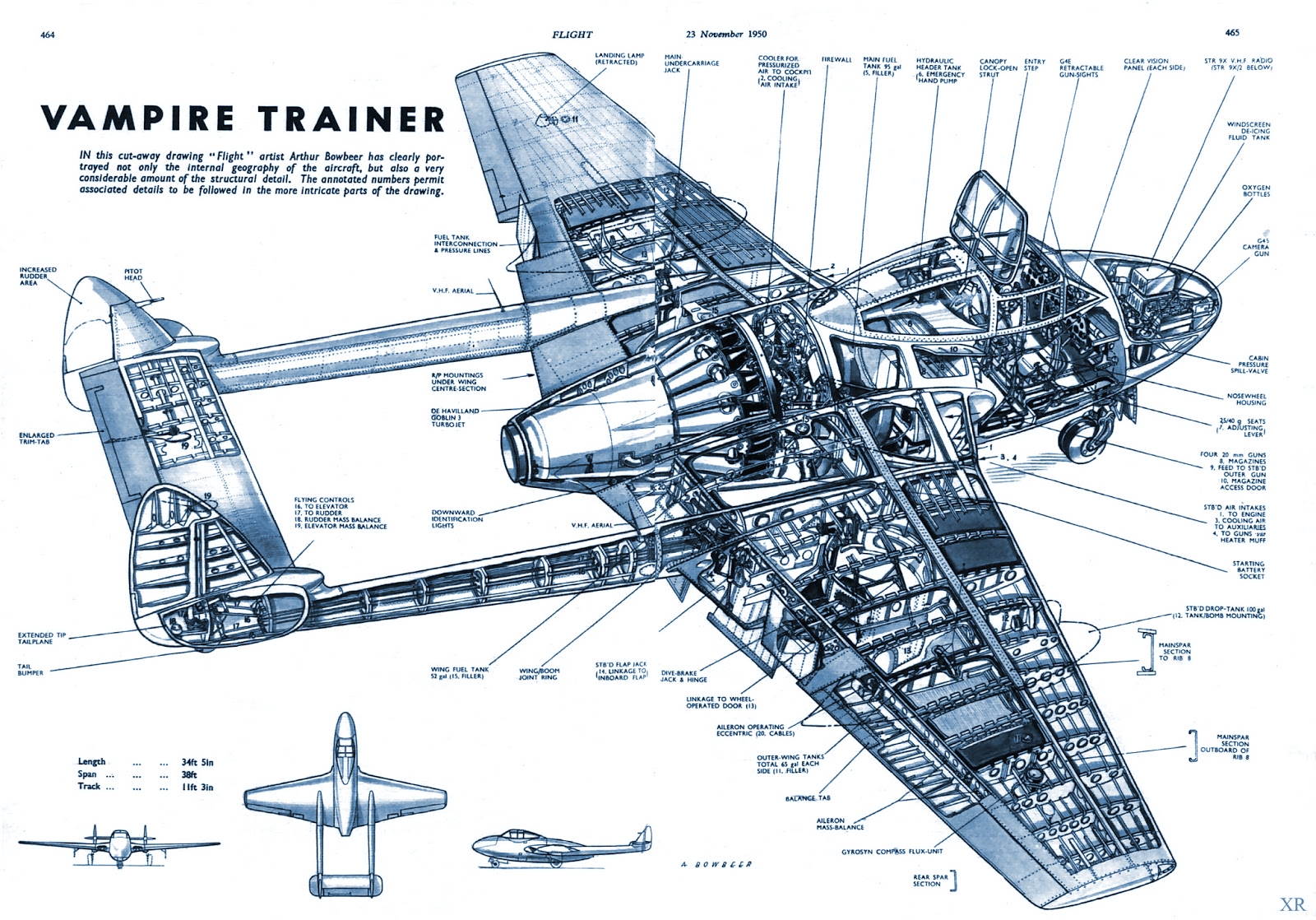

John: I’ve flown a total of 46 types of powered machines, fixed wing and rotary, starting in 1950, and a similar number of types of glider, starting at E.T.P.S in 1962. The list of powered machines: Aérospatiale Gazelle (1 & 2), Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma, American Champion Citabria, Bell H-13 Sioux, Blackburn Buccaneer (1 & 2), Boulton Paul Sea Balliol, Bristol Sycamore, Cessna 172, de Havilland Canada DHC-1 Chipmunk, de Havilland Dragon Rapide, de Havilland Sea Devon, de Havilland Sea Venom 21, de Havilland Sea Vixen (1 & 2), de Havilland Tiger Moth, de Havilland Vampire (T.11, T.22, F.5 & 9), Edgley Optica, English Electric Canberra, Fairey Gannet (3, 4, & 5), Fournier RF-5, Gloster Meteor T.7, Handley Page HP.115, Hawker Hunter T.8, Hawker Sea Hawk (2, 3, 4, 5, 6), Hiller HT Mk 1, Miles Magister/Hawk, NAC Fieldmaster, North AmericanT-6 Texan/Harvard, Percival Provost T.1, Percival Sea Prince, Piper PA-18 Super Cub, Robin DR400, Saunders-Roe Skeeter, Scottish Aviation Bulldog, Stampe-Vertongen SV.4, Supermarine Scimitar, Taylorcraft Auster V, Trago Mills SAH-1, Vickers Varsity, Vickers Viscount, Westland Dragonfly, Westland Lynx (1 & 2), Westland Scout, Westland Sea King (1, 2, 3, & 5), Westland Wasp, Westland Wessex (1, 2, 3 & 5), Westland Whirlwind (7,& 10). And the gliders: Akaflieg Braunschweig SB-5 Danzig, EoN Olympia 2B, Edgley A9, Eiri-Avion PIK-20, DG Flugzeugbau DG-1000, FFA Diamant 18, Glasflügel 206 Hornet, Glasflügel H-201 Standard Libelle, Grob G102 Astir, Grob G103 Twin Astir, LET L-13 Blaník, PZL Bielsko SZD-50 Puchacz, Rolladen-Schneider LS3, Rolladen-Schneider LS4, Rolladen-Schneider LS7, Rolladen-Schneider LS8, Scheibe Bergfalke, Scheibe SF 26 Super Spatz, Schempp-Hirth Discus, Schempp-Hirth SHK, Schempp-Hirth Ventus, Schleicher ASK 13, Schleicher ASK 18, Schleicher ASK 21, Schleicher ASK 23, Schleicher ASW 15, Schleicher Ka 6, Schleicher K7 Rhönadler, Schleicher K 8, Schneider Grunau Baby BII, Slingsby T.21, Slingsby T.30 Prefect, Slingsby T.31, Slingsby T.42 Eagle, Slingsby T.45 Swallow, Slingsby T.49 Capstan, Slingsby T.50 Skylark (2, 4 & 3F), SZD-8 Jaskółka, SZD-9 Bocian, SZD-22 Mucha Standard, SZD-30 Pirat, SZD-36 Cobra 15, SZD-51 Junior. RPS: In terms of flight characteristics and/or pilot workload, which of those was the most demanding? John: I was lucky enough, through fortuitous timing, to have two spells in 804 Squadron, the first a full commission flying the Sea Hawk, approaching obsolescence, then seven months on the Scimitar.

Although I enjoyed every minute of my 103 hours flying Supermarine’s exciting machine*, it has to be my choice in response to this question because it is only when embarked that the full range of aircraft operational options come into play in parallel with the full range of aircraft and ship limitations. The only single seater with this level of complexity and performance prior to the Sea Harrier, which I never flew, it also had a tendency to “pitch up” if handled carelessly; stalling and intentional spinning were forbidden.

- Interviewer’s note: 39 of the 76 Scimitars built were lost in accidents RPS: And the most forgiving/pleasant to fly?

John: Staying with fixed wing for the moment, I have to choose the new Hunter 8s we all flew to convert to swept wing, in my case just prior to flying the Scimitar at Lossiemouth. The word “smooth” springs immediately to mind – the axial compressor Avon engine, a huge step forward from the centrifugal Goblin and Nene, really good powered pitch and roll controls (the rudder was “manual”, more properly “pedal”), with excellent manual reversion. It “looked right and felt right” with an excellent cockpit layout and exterior view.

Among helicopters, I have to go for the Gazelle, a “smoothy” like the Hunter, and capable of 150 knots I.A.S.

RPS: What, do you think today’s Merlin and Wildcat pilots would make of pioneering FAA helicopters like the Dragonfly and Sycamore? John: I think they might be surprised that such rudimentary machines were ever employed in the operational roles assigned to them. Gas turbines, multi-engined configurations, autopilots and computerised engine controls have so improved life in the cockpit. A point on the Sycamore – my limited experience on it served to impress how the Bristol company were well up with the others in many respects, but how the Australian navy came to select it for use aboard ship baffled me, simply because the main rotor blade tips looked dangerously near the deck. RPS: Do you remember your first close encounter with an aircraft?

John: I believe it was a de Havilland Fox Moth operated by Cobham’s Flying Circus. One of my very earliest memories, when I must have been just three years old, was of a visit with my parents to a farmer’s field about one mile from our home in Tettenhall Wood, near Wolverhampton. I stood between my father’s knees in the cabin of a small biplane and saw our village from above during a short “joyride". RPS: They say no-one forgets their first ‘solo’. How did yours go?

John: True – of course it was magic. Mine, after plenty of dual practise, was a single circuit and landing in good weather at Pendeford, a grass airfield, in a Miles Hawk, a civil conversion of an ex-R.A.F. Magister (G-AHNV) operated by Wolverhampton Aero Club, five days after my first dual flight, in July, 1950. RPS: How many carriers landings have you made?

John: 248 (Sea Hawk 170D, 5N; Scimitar 50D; Sea Vixen 23), plus an unrecorded number in helicopters. RPS: Which was the most memorable? John: My 17th, on the 15th of July 1958, in a Sea Hawk aboard HMS Albion during work-up off the coast of Northern Ireland. I allowed the final approach speed (110 knots) to decay on final approach and sank on to the round-down, leaving a dent. The port main undercarriage leg collapsed and my hook engaged No.1 arrester wire. The aircraft flew again later that day. I was very embarrassed, of course, my C.O. recorded my misdemeanour in my log book, I was not punished, flew again the following day, and never made the same mistake again! RPS: What’s the secret of a good carrier landing?

John: Getting into the landing configuration in good time, carefully check the aircraft weight and decide on the correct final approach speed, then hold it all the way down to hook-on. The wind should be “down the angle”, so no drift, keep the power on until arrested to enable a climb-out in the event of missing a wire, or a wire failure, when full power should be applied until circuit height is resumed, then repeat above. RPS: Have you ever had to eject?

John: Yes, once, on 20 September 1957 from Vampire T.11 WZ496 en route to R.A.F. Valley from the Cheshire Plain after a low level map reading exercise with my instructor Flight Lieutenant Rufus Heald (see his book “Rufus Remembers” for his account, which fails to mention my name!) On reaching our transit height of 10,500 feet we both saw the engine bay fire warning light come on. With the engine shut down it was impossible to reach R.A.F. Shawbury, the nearest suitable airfield, in the 160 knot glide and I was ordered to jettison the canopy, then eject at about 1,500 feet a.g.l. My Martin Baker seat worked perfectly and I landed, uninjured, in a stubble field near a farmhouse not far from Wem. Rufus Heald damaged an ankle on landing in a farmyard nearby and was grounded for a time. I was flying again four days later. When the aircraft crashed, there was no fire. I believe we were Nos. 57 and 58 on the Martin Baker “successful ejection” list. RPS: Did simulators play any part in the life of a Fleet Air Arm pilot in the Fifties and Sixties? John: My first simulator, other than the Link trainer at R.A.F. Syerston, was the static one based on the Scimitar, at Lossiemouth, in 1960, really a high quality procedure trainer in which I spent four and a half hours. I flew the Buccaneer before the simulator was installed and converted on to Sea Vixens at R.A.E. Bedford without visiting the simulator at Yeovilton. The simulator on which I spent most time was the Sea King one at Culdrose. In the 70’s. RPS: Was your move into flight testing in the early 60s the realisation of a long-harboured ambition or the result of more prosaic factors?

John: I had been attracted by the idea of getting into test flying, but only if I could achieve it from within the R.N. Once I had completed my first squadron tour and moved on to the Scimitar, then to the very first Buccaneer unit in pretty short order, I was encouraged to apply for the ETPS course, and was successful. An important additional factor was that I thoroughly enjoyed flying in the Service environment and the tp qualification was likely to extend my flying career, and did so very effectively, especially after I moved on to helicopters. RPS: Of the various flight trials you were involved in, which had the most significant repercussions?

John: Hard to say because I didn’t stay in a single aspect of development flying, and moved on before the final outcome of trials in which I participated was achieved. I like to think lives might have been saved in Sea Vixen squadrons after the introduction of the deck landing autothrottle system, in which I had a hand, and likewise the head-up deck approach sight, with which I was involved at a rather earlier stage of its development. I’m not sure how far that one went, but I think it might have got into the Sea Harrier as an aid to approaching a safe hover beside the ship before moving over the deck to land on. At a very different level, the short burst of work in the far east in support of small ships’ Wasp flights having difficulty with torquemeter settings was important in its own way. RPS: You must have looked down on some spectacular scenery while “seeing the world” with the RN. Have certain vistas stayed with you?

John: Skye in winter on a beautiful sunny day from a Lossiemouth Vampire T.22 in 1959, the Lofoten Islands from my P.R. Scimitar in September, 1960 and the Southern Alps from my glider at 21,000 feet 14/12/1991. RPS: Do you miss the exhilaration and challenge of flying fast jets?

John: Yes, of course! However it was more important to me to continue flying for as long as possible, which I did by moving to helicopter testing, and, from 1962, gliding and soaring. After 3,000 glider flights totalling over 1,000 airborne hours I finally grounded myself in October, 2018. RPS: Given a magic wand capable of conjuring up a flight-ready example of any flying machine, what aircraft would you choose to take for a spin?

John: A difficult one! I’m torn between renewing my passport and soaring to even greater altitude in South Island, or revisiting Feshie Bridge in Strathspey to soar on a perfect Cairngorm day, again to great altitude, or finding a Hunter 8 for a final transonic blast in southern England. On balance, I think I’d probably go for Feshie. RPS: Thank you for talking to the Flare Path