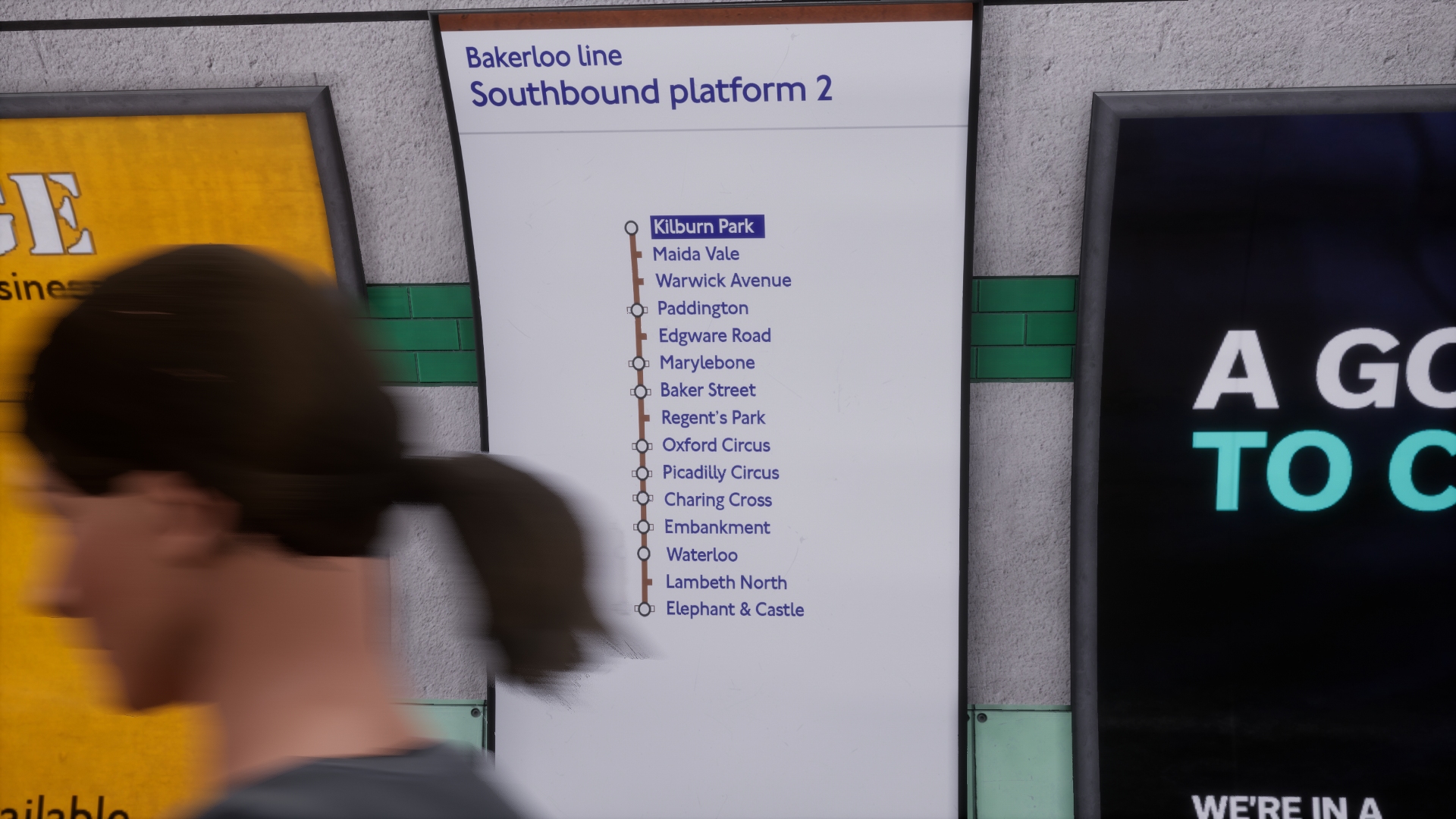

Our first break from the inky blackness comes at Kilburn Park, the most northerly of the Bakerloo’s subterranean stops. If Dovetail had modelled the station in its entirety I’d suggest we all alight here and go topside to admire the handsome tiled facade.

Unlike earlier tube station buildings (Kilburn Park opened in 1915 – part of the Bakerloo extension from Paddington to Queen’s Park) this one was built without a second storey because the go-ahead Underground Electric Railways Company of London had decided to abandon elevators in favour of a more modern technology – the escalator.

Today there are 451 impatient staircases on the Underground, the longest of which, the 61 metre-high flight at Angel, is positively dinky compared to some of the vertigo inducers on Russian metro systems.

Standing on the right so that in-a-hurry travellers can pass on the left continues to be de rigueur on the tube despite the fact that experiments suggest standing on both sides could reduce passenger congestion during rush hours.

One of the escalators at our next stop, Maida Vale, was used as a metaphor for disgrace and depression by a young film director called Alfred Hitchcock in 1927.

The chap on his way down physically, mentally and socially in the above sequence has just been expelled from his posh school and disowned by his aristocratic Dad after a bun shoppe shop assistant with a bun in the oven falsely accused him of being the father.

Just in case there are any robophobes aboard, I won’t embed the unforgettable but possibly NSFW video for The Chemical Brothers’ Believe, parts of which were shot at Maida Vale station. The fabulous one for Star Guitar (no Maida Vale but plenty of railways) will have to do as a substitute.

Leaving the first (and last?) station on the network to be staffed entirely by women, the headlight-impervious gloom envelops us again and the flange squeals die away. Having negotiated the long curve that allowed the Bakerloo to connect to the London and North Western Railway’s Birmingham line at Queen ’s Park and therefore run services all the way to Watford, we roll into Warwick Avenue, one of three stations on today’s leg that shares a name with a Top 10 (in the UK) single. A Flare Path flair point upholstered with genuine Made-in-Lithuania Bakerloo moquette to anyone who can, without help from Wikipedia, name the other two.

Not that you’d know it from peering out of the windows, just before Paddington and just after it we pass under interesting bodies of water. The Little Venice basin – a triangular lake formed by the junction of three canals – probably should have been called the Little Amsterdam basin. Although it’s changed a fair bit since Thomas Hosmer Shepherd sketched it in 1828, people looking to escape from Paddington’s concrete and cacophony still seek it out.

On the eastern side of Paddington station as we scoot under the Paddington Basin, the home of two of London’s quirkiest bridges and one of its strangest cinemas, I start applying brakes for Edgware Road, today’s fifth stop. If you ever arrange to meet someone “outside Edgware Road tube” be sure to specify which one. There are two completely separate stations, one on the Bakerloo and one on the Circle, District, and Hammersmith & City. Ours has the more appropriate location, the striking ‘green’ wall and fetching red tile facade, the other has the grim history and the amusing statue of the “I should-have-brought-a-longer-ladder” window cleaner opposite its entrance.

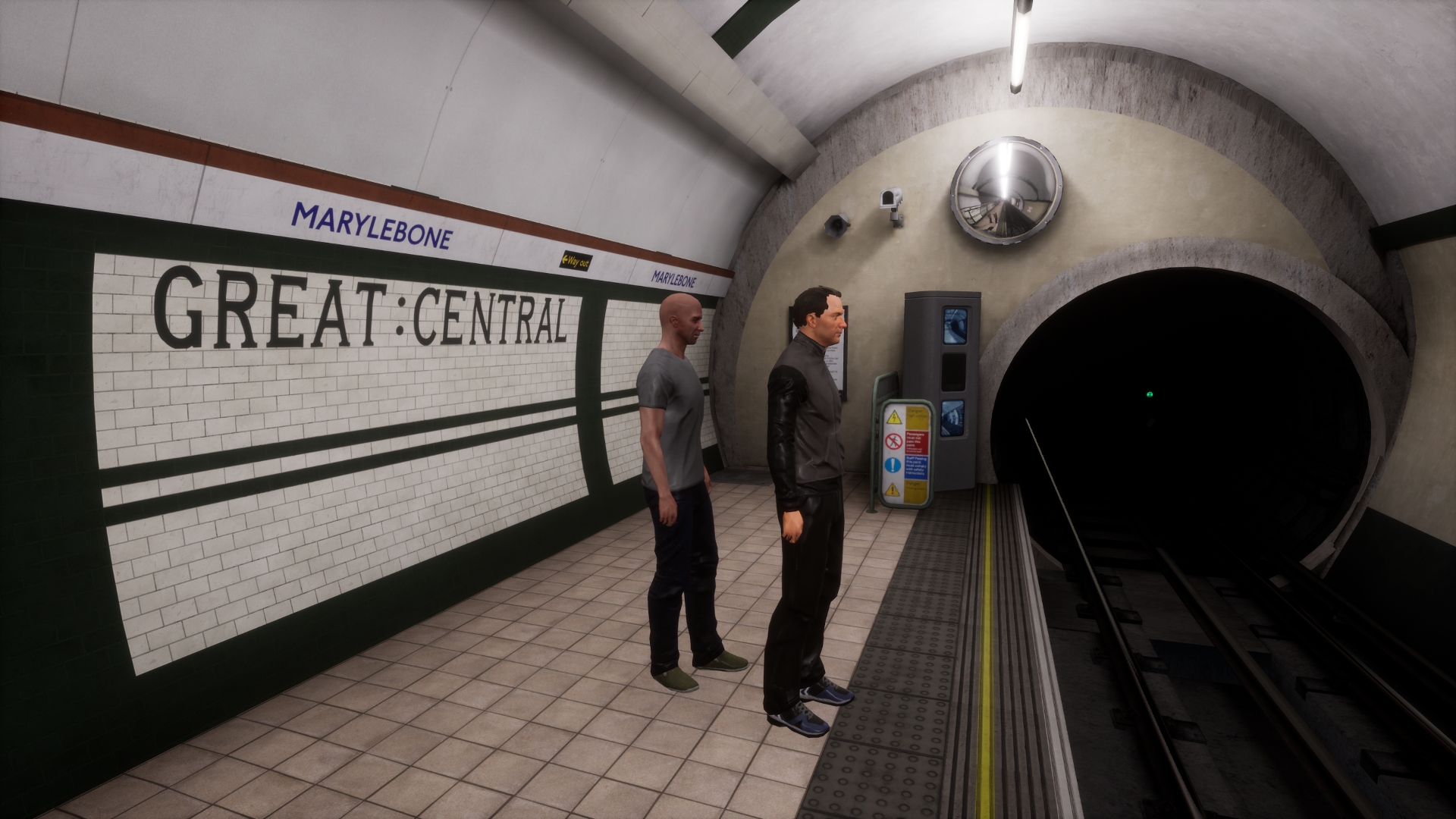

Let’s stretch our legs at Marylebone station. Follow me up these stairs, along this passage, and down these stairs to the northbound platform. Tucked away at the Edgware Road end is a bit of Underground archaeology – the name the station went under for the first ten years (1907-1917) of its life. While Dovetail’s recreation of the short-lived moniker isn’t perfect, it’s there which is more than can be said for many of the whines, growls, clicks and clacks made by real 72 Stock tube trains as they rattle along the Bakerloo. During the trip to Baker Street compare the faded threadbare tapestry of sounds woven by TSW2 to the glorious polysonic hullaballoo audible in videos like this one.

We pass directly under 221B, the Art Deco office block that began receiving Sherlock Holmes’ fan mail when Baker Street was renumbered in the 1930s (prior to the renumbering the street’s highest number was 85). If someone hasn’t already written a novel about the Abbey National secretary tasked with answering the great man’s post – a novel in which the protagonist eventually succumbs to temptation and starts accepting cases on behalf of Conan-Doyle’s creation – then someone really should.

When SH and his faithful chronicler occupied 221B, although the Bakerloo Line didn’t exist (Holmes retired to keep bees in the South Downs circa 1903 - three years before American railway magnate Charles Yerkes generated the funds required to complete the half-built first stage of the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway) London had a sizeable tube network and Baker Street a tube station. Indeed, the world’s first passenger-carrying underground railway, the Metropolitan, had been calling here since 1863.

References to the Underground in the canon are surprisingly rare. In only one story – The Adventure of the Bruce Partington Plans – does it play a significant role. If Sherlock ever swapped his habitual Hansom for a troglodytic train Dr. Watson fails to mention it.

A less famous Sherlock left Baker Street just last year. Ending an eighty-six year tenancy, the office that attempts to reunite the hundreds of thousands of items lost per annum on the capital’s public transport with their owners, relocated to South Kensington last October.

Forgive me if I pause a little longer than necessary at the southbound Bakerloo’s eighteenth platform. I have a special bond with the 170-hectare London lung that was in 1867 the site of a dreadful ice-skating calamity. In a sense I owe my very existence to Regent’s Park. My parents met while working as horticultural apprentices there in the late Sixties.

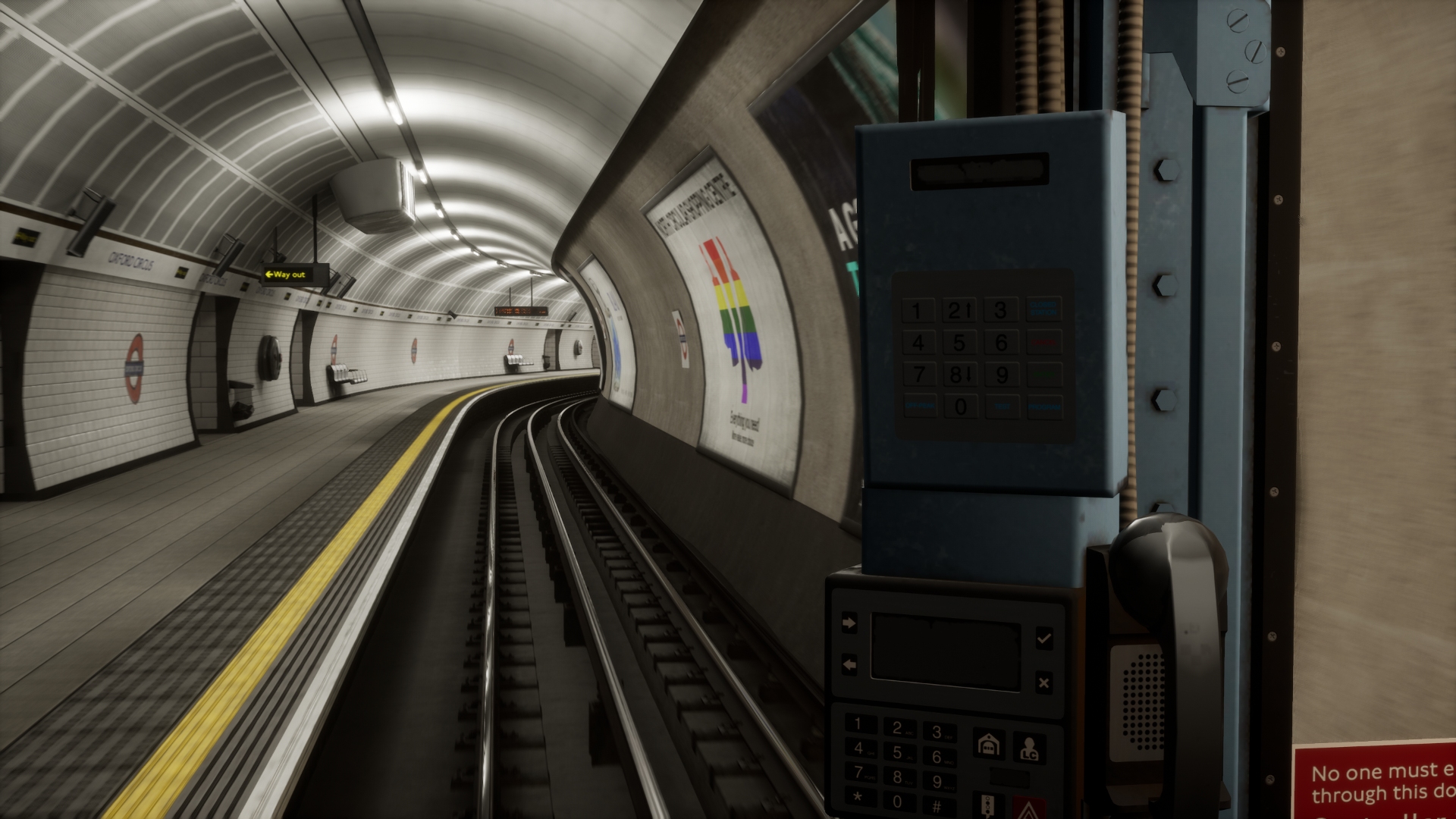

Leaving Regent’s Park we scurry southward, shadowing Portland Place, the street where Franklin Scudder met his end and England fast bowler Stuart Broad had a Scooby-Doo moment, at a depth of 23 metres until we reach Oxford Circus. TSW2 suggests the eye-catching green and white maze mosaics that once (?) decorated the walls of the Underground’s third busiest station have all been replaced by bland white tiling. It’s a while since I last stood on the prototype’s platforms, but I seem to remember seeing isometric labyrinths when I did. If any Bakerloo regulars are reading this, I’d be interested to know whether my memories are trustworthy.

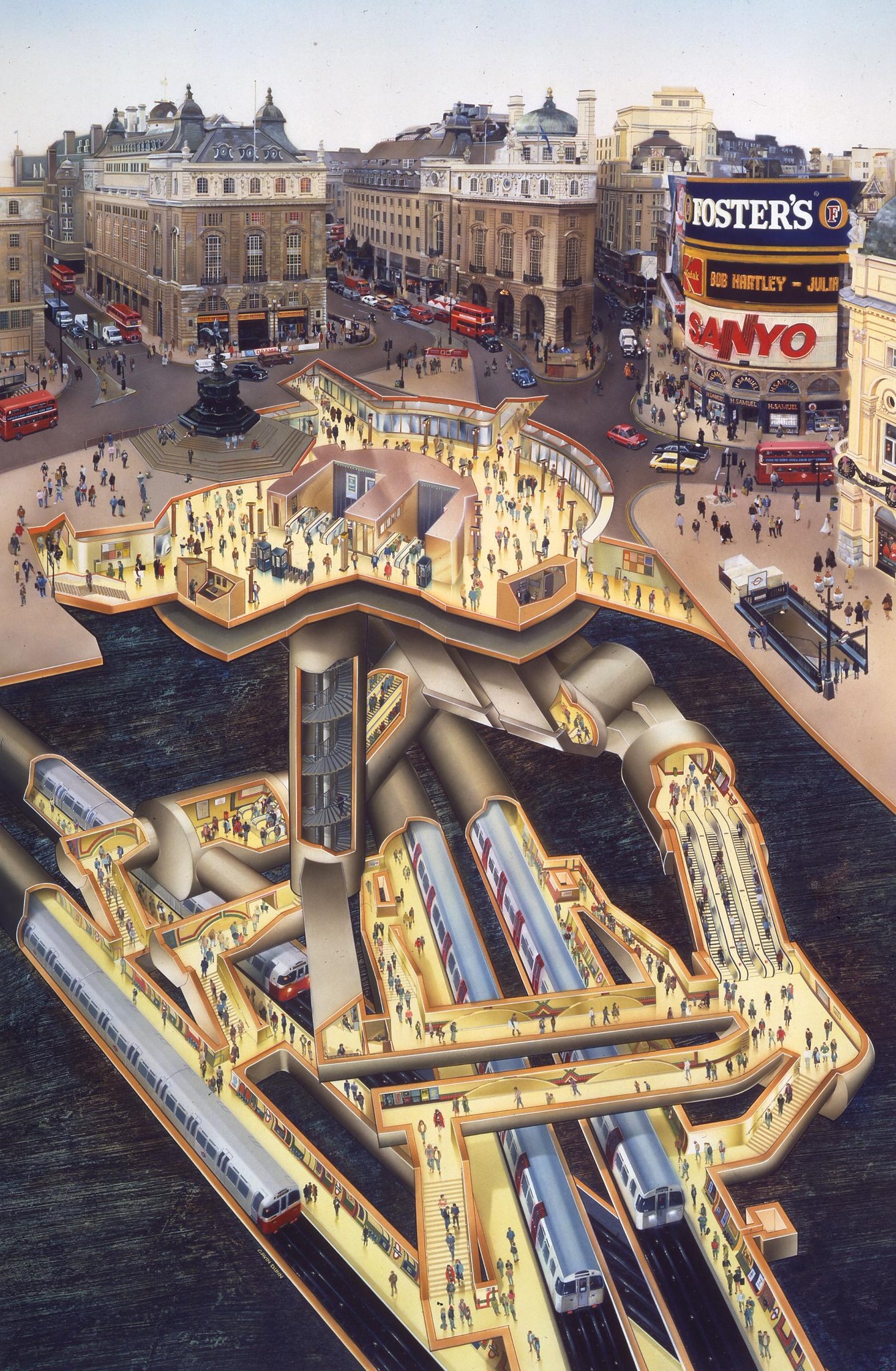

From Oxford Circus our metal road is in thrall to stuck-up Regent Street until we reach another circus, Piccadilly. The apparent modelling error visible through the windscreen at present is in fact a faithfully modelled station quirk. The Bakerloo’s determination to keep its northbound and southbound lines strictly segregated south of Kilburn Park wavers a bit here. A crossover combined with an unusual platform arrangement (Generally the two lines of deep-level tube stations share the same central passenger access points) give Piccadilly Circus’ northern end a glitchy feel.

In the cutaway above the two tracks on the right belong to the Bakerloo. Beneath them run the metals of the Piccadilly Line. Building the station’s impressive circular subsurface booking hall in the 1920s was a massive undertaking. Winged arrow-slinger Eros Anteros spent several years shooting pigeons in Victoria Embankment Gardens while the work was carried out. Pressed into service as air raid shelters and art vaults during WW2, passenger tunnels and service shafts rendered redundant by the remodelling still lurk behind Piccadilly Circus’ locked platform doors.

Before we squeal to a stop at Charing Cross we skirt Trafalgar Square’s southern fringe and pass within a metre or two of the dead-centre of the capital. British road signs that show the distance to London use this equestrian statue of Charles I as their “mile zero”. The statue stands on the spot once occupied by the landmark that gave this part of the capital half its name. One of the twelve ‘Eleanor crosses’ erected by the grief-stricken Edward I between 1291 and 1295, to mark the places where his wife’s funeral cortège stopped for the night during its journey from Lincoln to Westminster Abbey, the original ‘Charing Cross’ was torn down during the English Civil War.

My favourite tube station décor managed to survive Tottenham Court Road’s latest rebuild largely unscathed. My second favourite (pictured above) adorns the walls of Charing Cross’ Northern Line platforms.

The Bakerloo portion of Charing Cross relies on a selection of National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery (both nearby) reproductions for beautification in real life. In TSW2 there are white spaces where the art should be. Most disappointing.

Although strictly speaking a Northern Line story, I can’t stop at Embankment, the Bakerloo station closest to the Thames, without linking to this heartwarming BBC report about a widow drawing comfort from a 40-year-old Mind the Gap announcement.

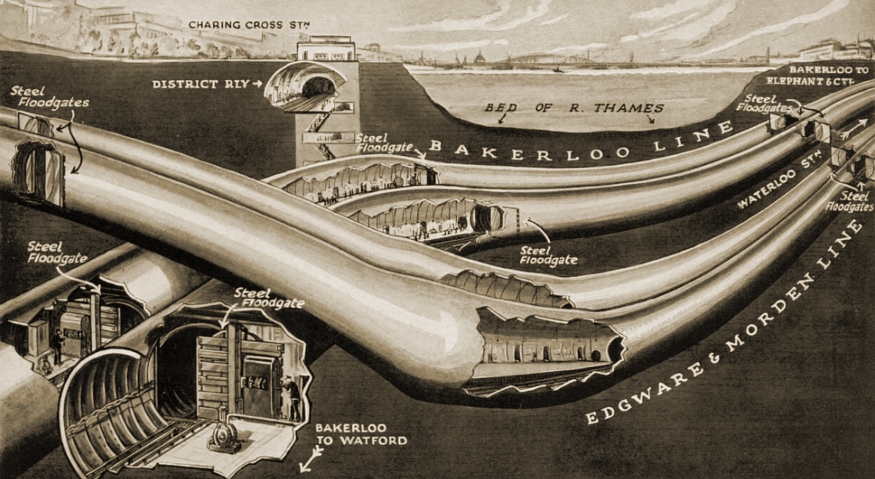

Counter-intuitively the line climbs as we leave Embankment and commence our subterranean crossing of the river. The Bakerloo’s proximity to the river bed doubtless made construction a little easier in 1906, but thirty years later the design decision caused headaches. In 1938 with war clouds gathering and Luftwaffe bombers expected over the capital, both the Bakerloo tunnels and the nearby Northern Line ones were temporarily sealed with concrete to prevent flooding.

Later electrically powered floodgates were installed providing a more flexible safeguard. The fact that a disused/sealed Underground tunnel close to Hungerford Bridge was flooded during the Blitz suggests that the measures were far from alarmist.

Compared to the Northern Line’s course into Waterloo, ours is somewhat serpentine. We weave into Platform 4, underpassing Jubilee Gardens, a South Bank space that in 1951 looked like the set for a lavish sci-fi movie.

Is there time for another grumble while we disgorge and gorge at Waterloo? I reckon so. How is it that Duke Nukem 3D boasted functioning CCTV cameras/monitors back in 1996 but TSW2 can’t manage the same in 2020?

Keep your eyes trained to starboard during the run to Lambeth North and you may just make out the spur that leads to the Bakerloo’s original depot. Still in use as a stabling point, London Road’s first trains – electric multiple units made in the USA but assembled in Manchester – had to be transported to the site by horse-drawn wagons because the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway had no links to other railways in 1906.

Satan shook this platform on January 16, 1941, injuring 28 and killing one of the locals attempting to sleep here. The closest station to the Imperial War Museum, Lambeth North is sited next to Britain’s most impressive Abraham Lincoln memorial and is a stone’s throw from the house where visionary poet/illustrator William Blake, the composer of the following oddly apposite verses, lived from 1790 to 1800. “There is a Grain of Sand in Lambeth that Satan cannot find Nor can his Watch Fiends find it: tis translucent & has many Angles But he who finds it will find Oothoons palace, for within Opening into Beulah every angle is a lovely heaven But should the Watch Fiends find it, they would call it Sin And lay its Heavens & their inhabitants in blood of punishment Here Jerusalem & Vala were hid in soft slumberous repose Hid from the terrible East, shut up in the South & West. The Twenty-eight trembled in Deaths dark caves, in cold despair They kneeld around the Couch of Death in deep humiliation And tortures of self condemnation while their Spectres ragd within. The Four Zoa’s in terrible combustion clouded rage Drinking the shuddering fears & loves of Albions Families Destroying by selfish affections the things that they most admire Drinking & eating, & pitying & weeping, as at a trajic scene. The soul drinks murder & revenge, & applauds its own holiness. They saw Albion endeavouring to destroy their Emanations.”

Having dampened the mood with that sizeable slab of Blake, I feel it’s my duty to conclude our trip with something uplifting.

The first baby born on the London Underground was born here at Elephant and Castle, the Bakerloo’s southern terminus (at present), on May 13, 1924. Behind a human screen formed by helpful city typists, Mrs Daisy Britannia Kate Hammond gave birth to a baby girl. Named Marie Ashfield Eleanor, rather than Thelma Ursula Beatrice Eleanor or Jocelyn – two suggestions from wags in the Press – the new arrival secured Lord Ashfield, chairman of the Underground, as a godfather. A statement made to the newspapers by the honorary dad, suggests he was no dewy-eyed sentimentalist: “Of course it would not do to encourage this sort of thing, as I am a busy man, but as this is so far as I know an event which is without precedent in the history of the Bakerloo, I think we ought to mark the occasion”.

Phew. Made it. This Flare Path rail tour terminates here. My colleague, Roman, is currently passing through the train holding an inverted bowler. Make for the platform sharpish if you feel two weeks trundling across sim London isn’t a great use of this column’s time. Drop a shiny coin or two into the titfer if you’re glad you hopped aboard 25 stations, 14.4 miles, and 379 facts ago.

To the foxer

title: “The Flare Path S Bakerloo Bimble” ShowToc: true date: “2023-01-25” author: “Brian Brant”

Seeing as no-one seems to have brought reading matter, digital entertainment devices, knitting, or tongues with them, and Dovetail’s scenery is somewhat lifeless, how about I leave the cab door open during the trip and regale you with topographical tidbits as I drive? I’ll take that stony silence as a “Go for it, Tim!”.

Bear with me. In order to ready this veteran electric multiple unit for use (1972 Stock is the oldest currently in service on the London Underground) I just need to insert the control key down here, pop the direction selector handle into the controller on the right (the controller on the left is a combined brake/throttle/dead man’s handle) and flip a few light switches on the other side of the cab.

Right, I think we’re now ready to trundle the couple of hundred yards to our first stop.

Harrow & Wealdstone, the northern extremity of the Bakerloo Line since LU services to Watford were discontinued in the 1960s, has an unenviable place in British railway history. It was here in October 1952 that the UK’s worst ever peacetime rail accident occurred. Three trains were involved as this Pathé news report explains…

Quite why the overnight Perth to Euston express ignored the one colour light signal and the two semaphore signals that were protecting the crowded commuter train waiting at platform 4, will never be known; the footplate crew responsible for the dreadful mistake were among the 112 people killed in the collision.

The footbridge dramatically severed by over-riding carriages makes it into TSW2 unlike the station’s lofty timepiece, the hands of which were shocked into immotility by what occurred at 08.19 on that fateful autumn morning.

Because the Bakerloo Line runs parallel to the West Coast Main Line here and shares tracks with London Overground trains, real-life Harrow & Wealdstone is a great place for train watching. I’d suggest you keep your eyes peeled for passing Pendolinos, Aventras, Desiros and the like if Dovetail had taken the trouble to model non-LU services. Sadly, they haven’t. Whoever’s calling the shots down at Chatham doesn’t seem to realise how much pleasure the average train simmer derives from ogling incidental traffic.

Kenton already? Alight here if you’re a fan of classic British TV comedy. A five minute stroll from the station is the leafy suburban road junction where Basil Fawlty gave a recalcitrant Austin 1100 Countryman “a damn good thrashing”.

The mock-Tudor semis that line Lapstone Gardens and countless other streets in this neck-of-the-woods were built between the wars by canny railway tycoons and opportunistic property developers. Kenton is part of ‘Metro-Land’, an (initially) rural strip of Middlesex, Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire speedily developed and cleverly marketed by the customer-hungry Metropolitan Railway (now the nearby Metropolitan Line). No-one wrote of life in this self-defeating suburbia more memorably than poet John Betjeman. Middlesex Gaily into Ruislip Gardens Runs the red electric train, With a thousand Ta’s and Pardon’s Daintily alights Elaine; Hurries down the concrete station With a frown of concentration, Out into the outskirt’s edges Where a few surviving hedges Keep alive our lost Elysium – rural Middlesex again. Well cut Windsmoor flapping lightly, Jacqmar scarf of mauve and green Hiding hair which, Friday nightly, Delicately drowns in Drene; Fair Elaine the bobby-soxer, Fresh-complexioned with Innoxa, Gains the garden – father’s hobby – Hangs her Windsmoor in the lobby, Settles down to sandwich supper and the television screen. Gentle Brent, I used to know you Wandering Wembley-wards at will, Now what change your waters show you In the meadowlands you fill! Recollect the elm-trees misty And the footpaths climbing twisty Under cedar-shaded palings, Low laburnum-leaned-on railings Out of Northolt on and upward to the heights of Harrow hill. Parish of enormous hayfields Perivale stood all alone, And from Greenford scent of mayfields Most enticingly was blown Over market gardens tidy, Taverns for the bona fide, Cockney singers, cockney shooters, Murray Poshes, Lupin Pooters, Long in Kensal Green and Highgate silent under soot and stone.

Talking of “taverns for the bona fide” South Kenton, the next station on our route, boasts – in reality at least – a splendid platform-adjacent public house. The Dutch-style Grade III listed Windermere has been urging Bakerloovians to “TAKE COURAGE” since 1938 and really deserved a bespoke structure in TSW2 instead of the generic brick one it’s ended up with.

Next stop, North Wembley. I believe that honey-coloured office block on the left is Dovetail’s nod to the stylish Art Deco factory that kept Britain masticating between 1927 and 1970. Almost all of the fields visible in this photo of the then newly built Wrigley chewing gum works would be colonised by Metrolanders in the decade that followed. By 1945 the area NE of the factory looked like this…

During our brief stop at North Wembley, why not enjoy one of the review code’s most entertaining bugs. If you’re lucky you may see a few passengers launched into the sky like bottle rockets on crossing the threshold between train and platform. I’m all for Minding the Gap but feel this degree of caution may actually be counterproductive.

If Sir Edward Watkin had had his way the most famous landmark visible from Wembley Central, stop number five, would have been a tower not a sports stadium. A serial railway entrepreneur, Watkin believed that Londoners would flock to use the Metropolitan Railway (of which he was chairman) if there was something stupendous waiting for them in bucolic Wembley. A vast pleasure garden dotted with bandstands, boating lakes, and sports facilities was deemed insufficiently stupendous on its own. What was needed was something similar to, but taller than (natch), the recently completed Eiffel Tower.

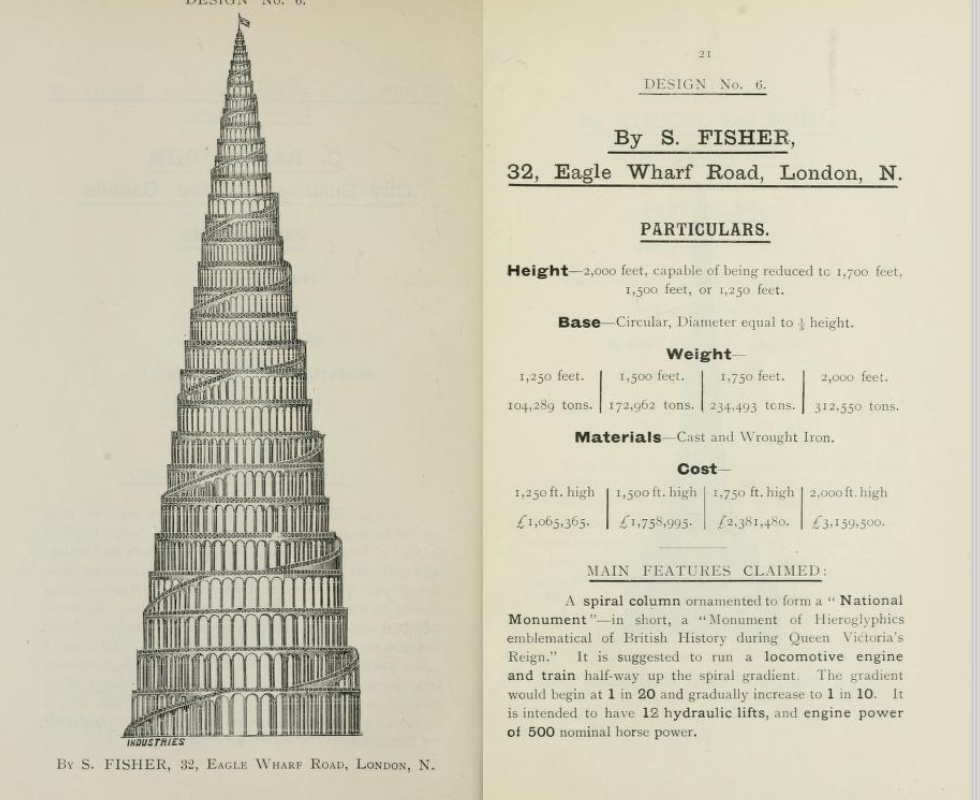

When Monsieur Eiffel refused the commission on patriotism grounds (“people would not think me so good a Frenchman as I hope I am.”) Watkin organised a design competition with a 500 guineas prize. There were 68 submissions in all. Sadly, designs such as S. Fisher’s…

“It is suggested to run a locomotive engine and train half-way up the spiral” J. H. M. Harrison-Vasey’s…

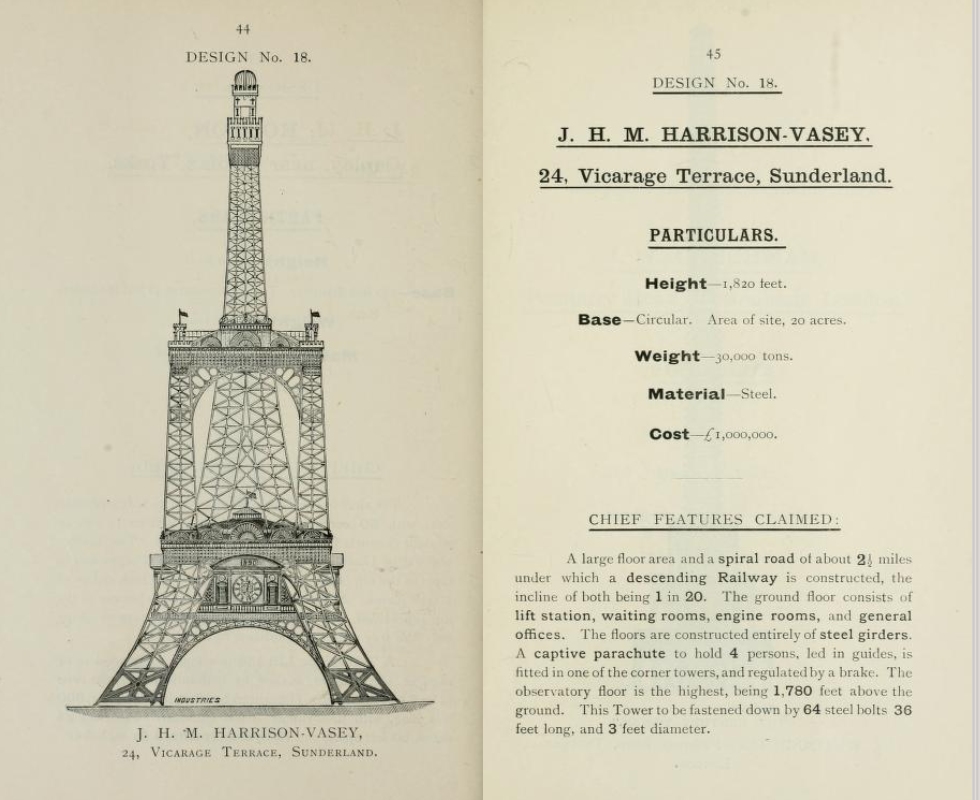

“A captive parachute to hold 4 persons, led in guides, is fitted in one of the corner towers, and regulated by a brake” and J. Tertius Wood’s…

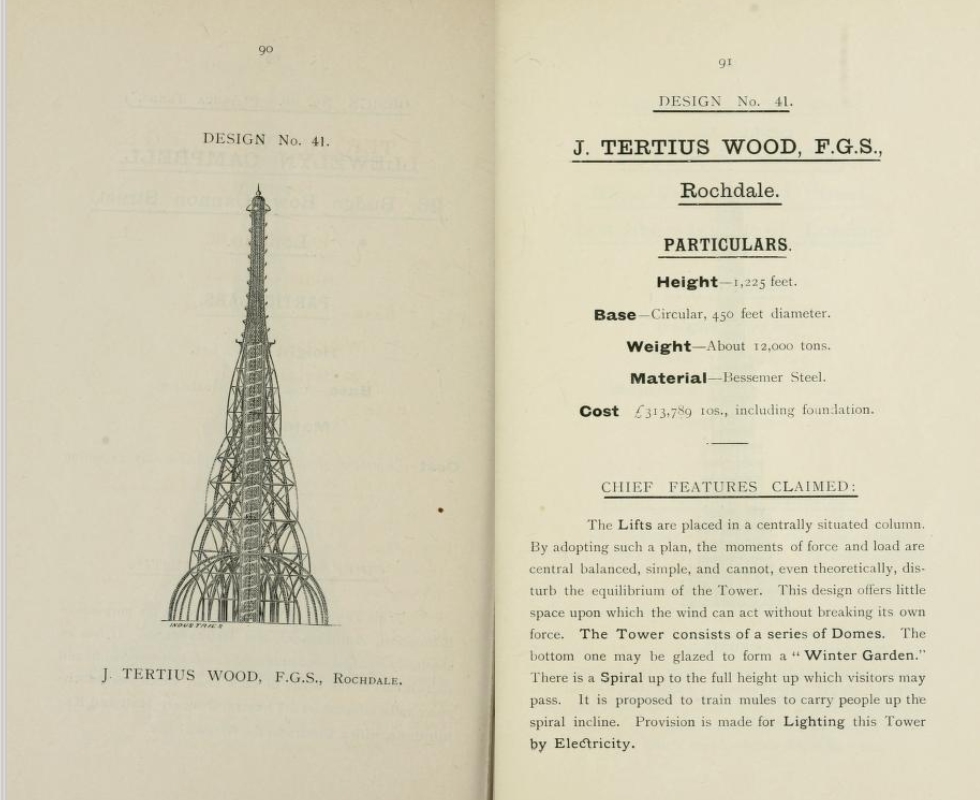

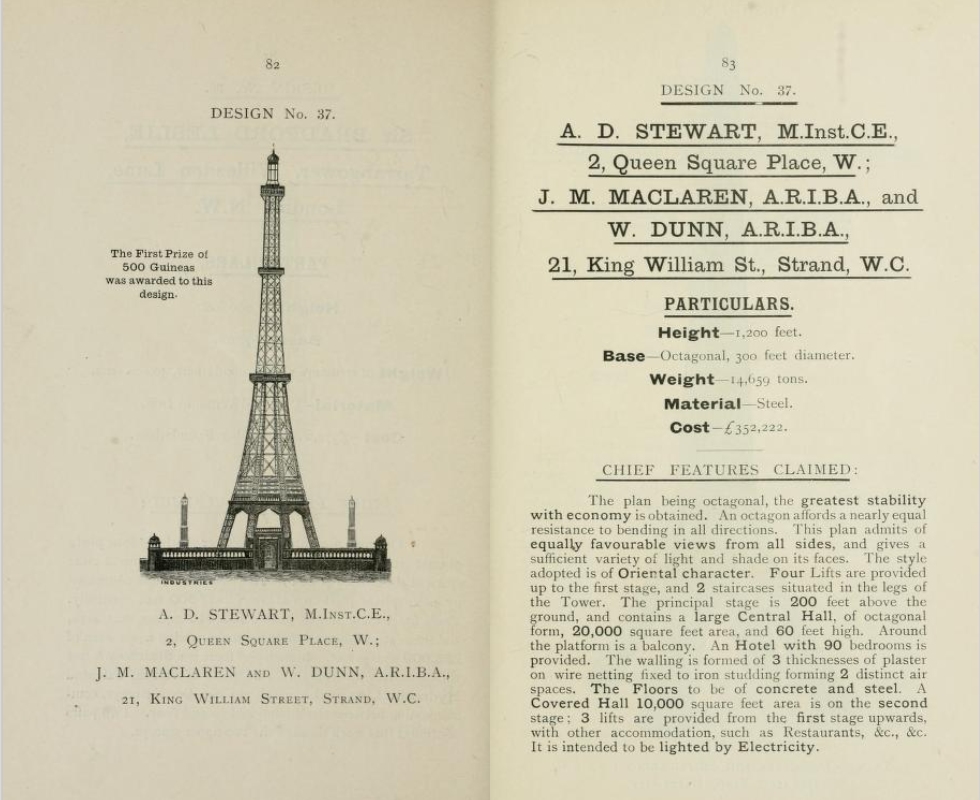

“There is a Spiral up to the full height up which visitors may pass. It is proposed to train mules to carry people up the spiral incline.” …were rejected in favour of a relatively conservative 1200-foot octagonal pagoda by a London firm.

Design #37 might have wowed the judges but investors weren’t overly enthusiastic. Funding difficulties led to the tower losing four of its eight legs before construction work began, and later subsidence issues combined with Watkin’s failing health meant that the unfinished structure was shorter than Nelson’s Column when finally abandoned in 1899. Dynamite removed the last vestiges of the pale pachyderm in 1907 and today the site is occupied by the home of English association foot-to-ball, Wembley Stadium.

Leaving Wembley Central we dart under the WCML emerging close to the Bakerloo’s main depot. In a minute or so we’ll be pulling into Stonebridge Park, the LU station you trudge to after some swine swipes your beloved Triton while you’re in the Ace Cafe demolishing a full English.

After Stonebridge Park comes Harlesden, when the wind is blowing from the SW, probably the capital’s most aromatic Tube station. The appetising smell comes from that big grey building over yonder. If you’re British and wheat tolerant you will definitely have eaten something baked in Europe’s biggest biscuit factory. McVitie’s Rich Tea, Chocolate Hobnobs, Digestives, and chocolate digestives… they all hail from Harlesden. Britons consume over 71 million packets of the latter every year (roughly 52 biscuits per second). While my contribution to this sterling effort has dwindled of late, I try to help out whenever I can.

Not all of the bombs that ravaged this part of Greater London during the last war were made in Germany. A few had local origins. Between January 1939 and March 1940 the IRA planted 300 infernal machines on the British mainland. The targets of the ‘S-Plan’ (S = sabotage) were largely infrastructural but ten people died and around a hundred were injured as a result of the campaign. In Harlesden a bridge carrying electricity cables across the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal was hit. In Stonebridge Park an aqueduct was molested. In Willesden (our next port of call) the bombers had a go at a railway line.

The towering container cranes dashing past on our right at present have more than substantial steelwork and quadrupedalism in common with Watkin’s Folly. The massive freight yard they loom over was built to handle a stream of Eurotunnel freight trains that unfortunately never materialised. Dovetail fail to acknowledge that three of the four track-straddlers were demolished early last year in preparation for the yard’s new role as an HS2 construction hub and that all wore striking yellow paintjobs.

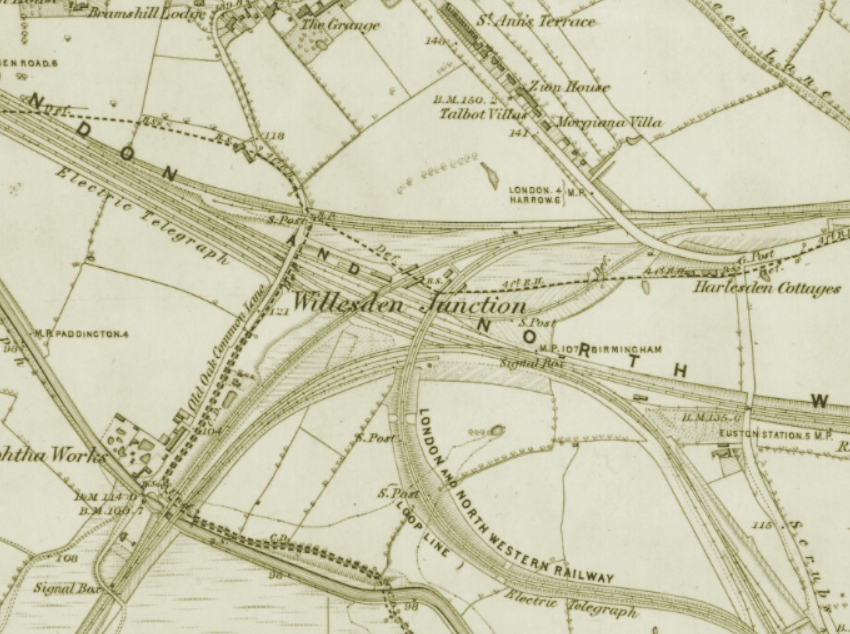

Willesden Junction station is a complicated affair. We’re using the lower portion. A couple of minutes after departing the high-level part, southbound trains cross the line featured in the first Flare Path rail tour on their way to either Acton Central or Shepherds Bush.

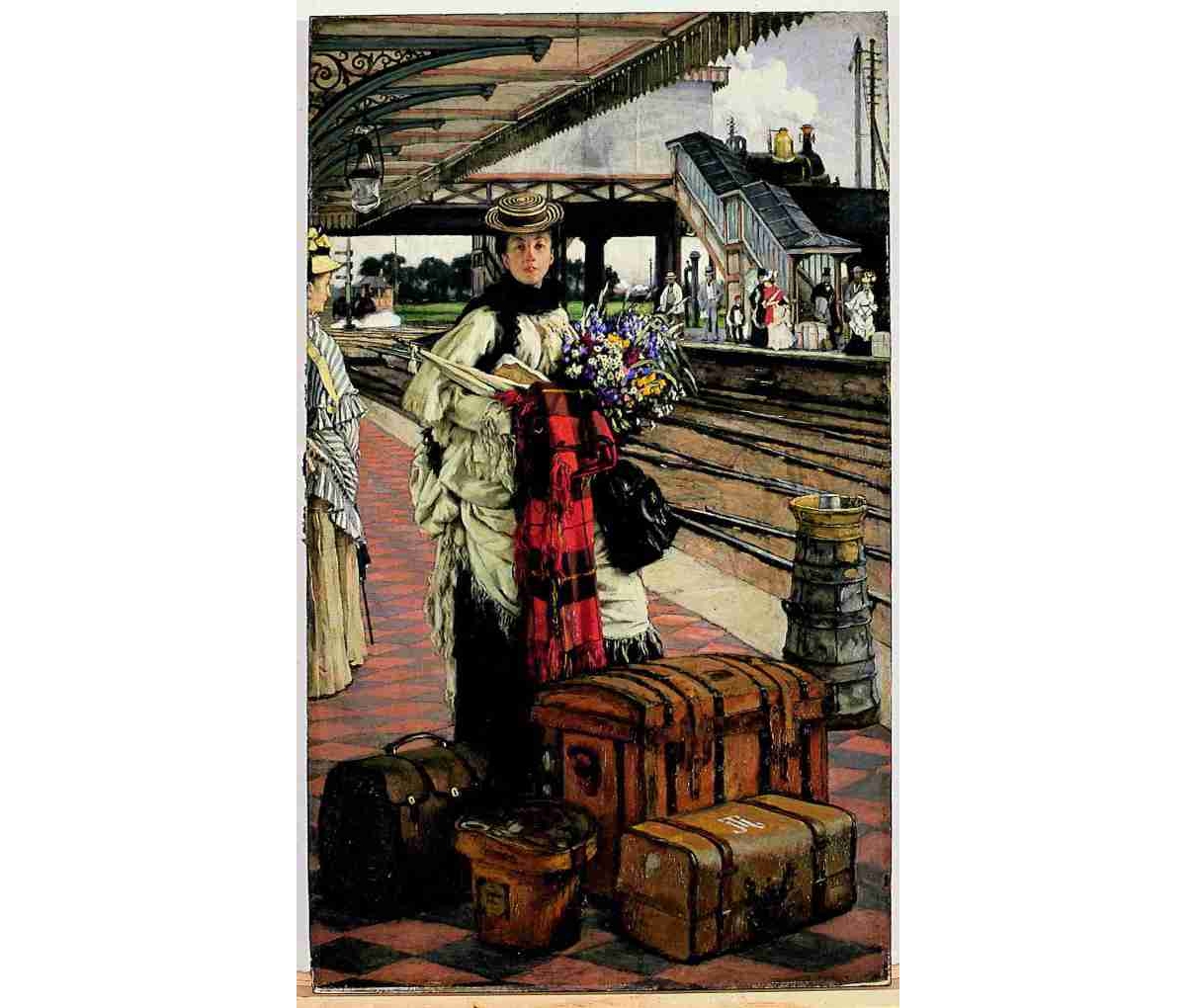

When James Tissot painted a prodigiously luggaged traveller waiting for a connection at Willesden Junction in the early 1870s, although the site’s tangle of lines was already well established, the station was still surrounded by hedge-hemmed fields…

TSW2 implies that a tract of this farmland just to the east of the junction survives to this day. Actually the green space unfurling on our starboard beam is Kensal Green Cemetery, one of the capital’s ‘Magnificent Seven’ boneyards. Among the luminaries dirtnapping there are Victorian storytellers Anthony Trollope and Wilkie Collins, engineer par excellence Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Niagara daredevil Charles Blondin, and Overclockers’ first customer Charles Babbage.

This 320-yard tunnel leading to Kensal Green station gives a taste of what’s to come beyond Queen’s Park, the last surface stop on the southbound Bakerloo. Subterranean lighting isn’t one of the sim’s strong points, regretably. Want shiny rails and sooty brickwork plausibly illumined by jiggling headlights and sudden arc flashes? With luck they’ll make it into TSW3 or 4. My favourite bit of the entire route is imminent. Approaching Queen’s Park, true to prototype, we beetle through a train shed…

And beyond the station, pass a fetching facade before descending a surprisingly steep bank into the bowels of West London.

In the early hours of 19 February 1984 a train sped down this slope with no-one at the controls. The runaway, which had somehow managed to slip its overnight moorings at platform 2, narrowly missed four track workers before scuttling underground like a spooked centipede. Gathering speed as it clattered through Kilburn Park, Maida Vale, Warwick Avenue, Paddington, Edgware Road, and Marylebone, it was eventually brought to a halt 5.7 kilometres from its starting point by a combination of the incline between Marylebone and Baker Street and the sharp bend at Regent’s Park.

I hope to get a little further than that restless rambler when I start exploring Bakerloo’s darker reaches next week. Join me next Friday for more TSW2 observations, Tube trivia, and extracurricular history.

To the foxer