You start as the manager of a brand-new zoo, and after a few tutorial screens you’re left with a blank canvas of land and the freedom to mould it any way you want. You start with two main ways to gain new animals: rescuing them from an independent shelter, or trading with other zoos across the globe. Eventually attendees come to see these animals, and your goal is to keep everybody happy and make tons of money along the way.

Let’s Build A Zoo embraces the chaos that I imagine running a real zoo would involve. The greatest strength of the game is how all of its systems work alongside each other. You’re given a lot of individual control over your park – right down to the amount of corn syrup in the candy you sell. But, as in the best management games, these minute decisions often have knock-on effects that you want to plan around, turning into a giant version of the board game Mouse Trap.

If you put more chilli seasoning in your food it’ll increase your customers’ thirst, which might lead them to buy more cola. You’ve rigged the cola to have extra caffeine, though, which gives people more energy. Now they’ll end up spending more time and money at the park in general, and your pockets get way deeper. After a while, it feels like your zoo’s actual inhabitants are the people.

Watching these systems interact is when Let’s Build A Zoo is at its best, and playing around with them is encouraged by the addition of an in-game morality meter. You’re given multiple “critical choices” throughout the game that present some sort of moral dilemma. You’re often given only two decisions to choose from: one that benefits you in the short term but lowers your morality score, or a more charitable action that does little other than raise that same score.

When it’s very early on, these choices can make or break your zoo. Nobody wants to see your geese? Why not just paint one of them so it looks like a peacock? Make it your star attraction! You get money, the people (think they) see a peacock, everybody wins! Sometimes the odd visitor would comment on how my peacock was clearly fake, and that made me question what I was doing more than any morality meter, and despite any amount of money I ever made. Of course, the “peacock” was nothing but a short-term solution, and when it died of old age I was left in the same predicament as before. Only now I had an entire flimsy house of cards I had to stop from falling over.

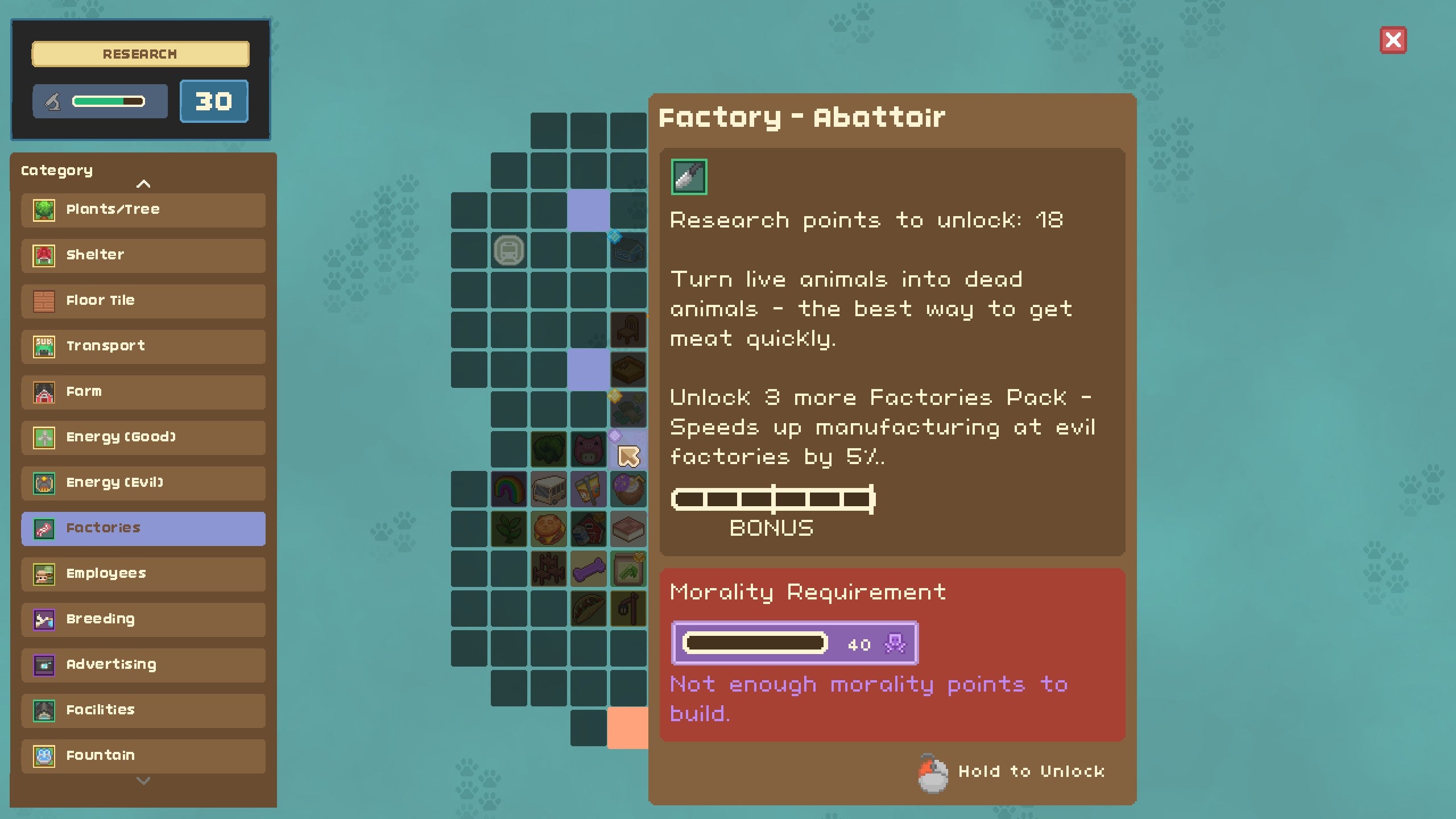

Depending on the moral affinity you choose, you unlock one of two tech tree paths for you to take your park down. One leads to sustainable farming and renewable energy, and the other sees you turn your zoo into a conveyor-belt style abattoir.

This sounds quite reductive as a system and… that’s because it is. But Let’s Build A Zoo is so self-aware in what it’s doing that the morality system ends up one of the best parts. By reducing morals to a number and gating certain unlocks behind it, it becomes just another system for you to manage. Oh, somebody died in our zoo? Ehhh… just plant a few more trees and people will forget about it. The game engages in a second meta-subtext layer of morality that’s actually kind of disturbing. Just how much value can I really squeeze out of this park? And how much am I willing to actually do?

That’s not to mention the ethical issues Let’s Build A Zoo raises by giving you access to CRISPR technology to gene-splice animals together. Yes, that’s right, you can fuse any two animals together to create whatever you want. Do you like rabbits? Do you like pigs? Why not merge them together so you can have the head of a pig on the body of a rabbit? It’s the best of both worlds!

The splicing isn’t the main focus of the game, but it adds a welcome diversity to animal husbandry that I really appreciate. Let’s Build A Zoo is always throwing new things at you without letting the previous stuff get stale. It gives the game a bizarre energy, like you’re in the circus running back and forth spinning plates on sticks - but in a weirdly relaxed way.

The soundtrack to Let’s Build A Zoo adds to this, as it always perfectly complements the atmosphere of the game. It’s a set of ambient tracks that are simultaneously up-beat, rhythmic, but also slightly menacing. It adds a consequential depth behind every decision you make in the style of FTL: Faster Than Light.

Although with a game that has so much on display at any time, I found myself wishing that Let’s Build A Zoo’s menus were a bit more streamlined. There’s already been two patches that have smoothed things out, but I think some areas like managing your staff or your animals could do with less menu interaction. I can see this sort of thing becoming an unwieldy problem down the line once you have thousands of in-game days.

Let’s Build A Zoo has a deeply absorbing core that it builds from, and its more unique elements do enough for this game to stand on its own in a crowded genre. I’d recommend it to most people, even those who think it doesn’t appeal to them. I’m normally terrible at these games, and end up throwing, like, fifty benches in a corner to fulfil some level criteria as quickly as possible, but even I love Let’s Build A Zoo. Plus, just like any good tycoon game, I came out of it slightly ashamed of my behaviour.